“By the time of birth, the train has left the station. This does not mean it cannot be stopped in its tracks, but it generally cannot be sent back to the station.”

-McCarthy et al

One of the foundational statements of Transgender Ideology, particularly regarding the medicalization of children, is the concept of “the wrong puberty.” The abbreviated version of this concept is that somehow the brain or soul is sexually mismatched from the body and that medicine can force the two into alignment by altering the body. A necessary step in this alignment is preventing the damage “caused by the wrong puberty.” In essence this position relies on the belief that up until puberty girls and boys are the same, that physical dimorphism is only due to sexual maturity and that behavioral differences are entirely social - unless of course they are due to the magic of “gender”.

Of course, it won’t surprise readers that this belief is rooted in something other than physical evidence.

At the shallowest level boys and girls appear very much the same until girls commence puberty - for instance, the growth charts are nearly identical for young boys and girls, physical secondary sexual characteristics are not as pronounced as they will be, and they seem to hit the same development milestones at roughly the same time. In comparison to adults, children of both sexes appear to be the same - they have neither breasts nor facial hair, neither wide hips nor developed muscles and they know nothing of sexual drive; however, if one looks more closely girls and boys are quite different. You can convince yourself that boys and girls are the same until puberty only if you ignore the elephant-in-the-pants (genitalia), gloss over subtle but very real physical differences and ascribe all behavioral differences to socialization.

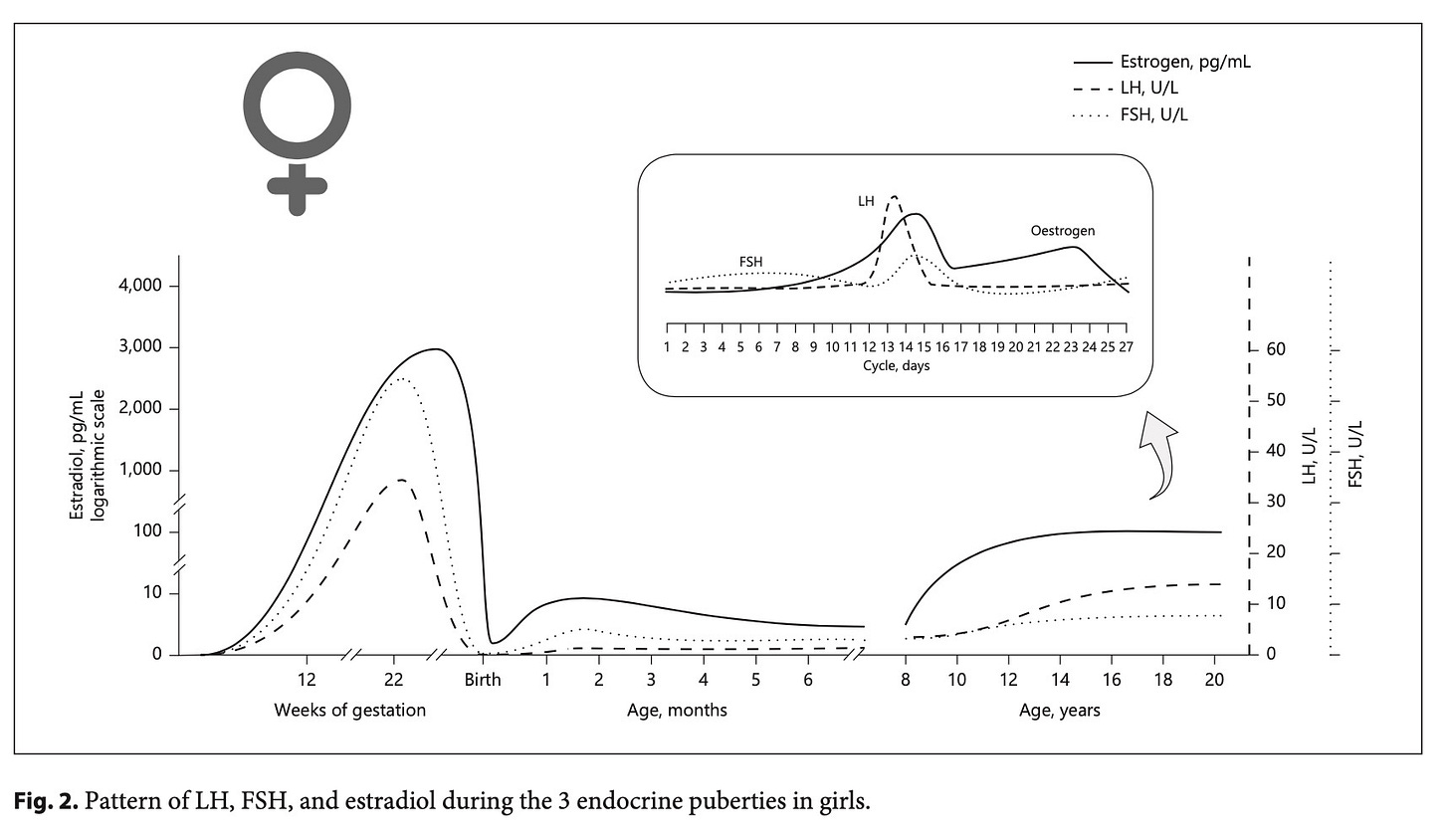

But what is puberty? In simple terms, it’s a flood of hormones that bring about significant physical and mental changes. We tend to think of puberty as the rise of testosterone in boys and estrogen in girls, but it’s actually a much more complicated shift in the Hypothalamus -Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) Axis. This axis includes hormones that you probably didn’t know existed – such as Lutenizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH) – but are essential components of the puberty system. Although both sexes will be exposed to LH and FSH, the timing of the hormones and the levels are significantly different and the developmental effects on males and females are also different.

We don’t need to get into the complete workings of HPG Axis, but do understand that there is far more going on in puberty than just testicles producing testosterone and ovaries producing estrogen. Modern science is starting to understand how infants are exposed to hormonal surges during gestation and in the days and months immediately after birth. The gestational exposure isn’t considered a puberty because it is part of the development of a zygote into a recognizable human being. There is a lot of evidence that boys and girls have quite different gestational paths and interrupting the path prevents normal development.

Complicating our understanding of hormones in puberty, babies have surges in hormones immediately after birth! The first months after birth are now considered a “mini-puberty” as it is a distinct period of tremendous hormonal influence. Yes, that little baby boy is experiencing testosterone levels that may be as high as an adult male! Baby girls undergo a subtler but longer exposure to estrogen.

Let’s take a quick look at some graphs of the levels of critical hormones during development. The first pair of graphs are taken from Becker & Hesse and the second pair of graphs are taken from Bizzarri & Cappa.

These graphs largely tell the same story of mini-puberty but with some interesting details. Becker & Hesse show three periods of exposure: gestation, mini-puberty and puberty. Note that boys get doses of testosterone earlier than girls receive estrogen, and the doses of estrogen are significantly lower during mini-puberty and teen puberty than during gestation. Bizzarri & Cappa demonstrate how boys have a brief (only 12-24 hour long) surge of Lutenizing Hormone before a similar surge of testosterone immediately after birth. After a brief rest, both LH and testosterone begin a steady rise, marking the commencement of mini-puberty in boys.

Both sets of graphs show far more than just differences in estrogen/estrodial and testosterone. LH levels are much higher in boys, while FSH has a reversed role and has a stronger presence in girls. Bizzarri & Cappa also show another pair of hormones – AMH & Inhibin B – that are present for boys from late gestation through mini-puberty while girls get only a fraction of these hormones and only months later. For our purposes, these charts serve as a stark reminder that boys and girls are not the same! Not only are testosterone and estrogen/estradiol not mirror images on an assembly line where we have to decide at X weeks of development to add one or the other, but the sexes develop differently - exposures to testosterone and estrogen are not equal in timing or duration, nor are exposures to other HPG axis hormones equivalent.

Or, starting somewhere around the 10th week of gestation the sexual dimorphism trains have left the station on two very different tracks.

Since teen puberty is so clearly noticeable, why aren’t the physical effects of mini-puberty more obvious? Unlike teen puberty, mini-puberty doesn’t usher in strong. observable physical differences. Instead the effects may be considered foundational in that the changes prepare the body for the dimorphisms that puberty will bring, and also create cognitive differences which, for obvious reasons, aren’t obvious in a four month old baby. Much of the research interest in mini-puberty has been trying to connect levels of testosterone or estrogen to observable differences - and some of the findings are given below. This vein of research is helping to understand variations within the sexes. Basic physical differences between the sexes also exist although these are not tied to differences in gestational exposure or mini-puberty. (Research has been done on animal brains that, for obvious reasons, hasn’t been replicated with humans, and despite the difficulty of measuring behavioral differences in babies the literature of early dichotomy from these hormones is accumulating.)

Let’s look at some potential areas of sexual dimorphism as they relate to mini-puberty:

Gonadal Development - For boys, mini-puberty testosterone levels are correlated with testicle and penis growth. Further, during mini-puberty a type of cell in the testicle (Sertoli) increases dramatically - these are the cells that will later be critical in spermatogenesis, and thus much of male reproductive health is dependent on developments in mini-puberty. Girls don’t undergo much, if any, change in sexual organs during mini-puberty, but some results suggest mini-puberty affects mammary gland growth.

Body Composition - Boys experience a negative correlation with mini-puberty hormone levels and weight, at least until the age of six. Animal research suggests that mini-puberty hormone exposures also program the placement of body fat in later life. Boys are observed to be longer and heavier than girls at birth and at five months, and they also add more lean mass (muscle and bone) than girls.

Behavior - While many parents are certain that boys and girls have different behaviors, the research is too thin at this time to associate the differences with mini-puberty. Some studies suggest an effect, but others find none. For this one, rely on your own anecdotal evidence!

Cognitive Development - It’s very hard to measure early cognitive growth, but there are clear effects of mini-puberty moderating language development skills. Girls develop pre-cursors to language development and show greater base language abilities sooner than boys.

In addition, it’s relatively easy to find measurable physical and behavioral differences in pre-pubescent girls and boys - although these are not proven to be caused by hormonal changes. Two simple differences are height and bone density. While girls and boys appear to be the same height, there is a small but significant difference in the mean height that is obscured by the overlapping distributions. Going inside the body, precise scans of the hip in boys and girls show that the boys in Tanner I or Tanner II stages of puberty have denser bones and thicker bones (essentially the strength of the bones) than girls at the same Tanner level. Indeed, on average Tanner I & II boys have stronger hip bones than older Tanner IV & V girls. While it is reasonable to conclude that boys’ skeletons are preparing for greater muscle mass. the more important takeaway is that pre-pubescent children have deeply hidden physical dimorphism. The astute reader will also have already reached the conclusion that even a pre-pubescent boy may have a skeleton that is athletically superior to those of older teen girls and young adult women - and puberty blockers can’t change that.

So, what do we now think of the “wrong puberty” idea? The HPG hormones that define teen puberty actually start within weeks of conception and continue in the first months of life before going dormant until about the age of 8. This exposure lays down a dimorphic foundation upon which further physical and cognitive development will occur - and that foundation cannot be undone or modified. Against this backdrop the idea of “wrong puberty” is nonsensical, with teen puberty merely the conclusion of a process that has been proceeding for the child’s entire life.

As the quote states… the train has left the station and it can’t go back. It can only proceed along its path.

Sources:

Becker M, Hesse V. Minipuberty: Why Does it Happen? Hormone Research in Pediatrics. 2020;93(2):76-84. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32599600/)

Bizzarri C, Cappa M. Ontogeny of Hypothalamus-Pituitary Gonadal Axis and Minipuberty: An Ongoing Debate? Frontiers in Endocrinology (Lausanne). 2020 Apr 7;11:187. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32318025/)

McCarthy MM, Herold K, Stockman SL. Fast, furious and enduring: Sensitive versus critical periods in sexual differentiation of the brain. Physiology and Behavior. 2018 Apr 1;187:13-19. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29101011/)

Sayers A, Marcus M, Rubin C, McGeehin MA, Tobias JH. Investigation of sex differences in hip structure in peripubertal children. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010 Aug;95(8):3876-83.(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2917783/)

And thanks to an expert, a professor in the area of development and hormones who wishes to remain anonymous, for discussing these issues and converting the arcane into the common.

As a scientist, I am constantly face-palming when I hear trans activists claim that cross-sex testosterone or estrogen “transform” them into the opposite sex. All it does is deform them into a parody of the opposite sex. As the info in this post shows, sex is not fluid or changed via mutilation.

A wonderfully informative essay. As a biological psychologist, I appreciated you including so many generally little known facts. In support of your overall thesis, I would add that (as you clearly know), it's even more complex and intricate than your (very good) overview suggests. And, every time I read a piece such as this, I am reminded of how little I know compared to the amount of information that is available, and is being discovered daily. It's astounding to me the degree to which the ideologues are fueled by intellectual hubris, and an ignorance (or fundamental misunderstanding) of biology. I commend you for taking the time and effort needed to present such an intriguing essay. I hope that it is widely read and appreciated. Sincerely, Frederick